Fethard Historic Town Walls County Tipperary.

The medieval town walls are of outstanding significance for defining the area of medieval settlement.

Former President Mary Robinson Visited Fethard in 1993

She speaks to the relevance of the work being undertaken by the Friends of Fethard

on the restoration of the Town Wall along the river bank.

Medieval History, 12th – 14th centuries Little is known of pre-Norman settlement in the Fethard area, and the site of the town may have been occupied for the first time by the Normans. King John’s grant to Philip of Worcester has been mentioned above, but it was perhaps only after the Norman baron William de Braose (established in England at Bramber) was granted the Tipperary barony of Middlethird by King John in 1201 that the borough was established at Fethard. By the time that William was giving property in Fethard to the Dublin Hospital of St John he could refer to ‘my borough’, and when he also gave the parish church to the Hospital in 1208 the place must have been reasonably established, if not fully settled. However, when the Braose lands were confiscated by the crown in 1208 he had not yet built a castle. It has been suggested that in 1215 the Archbishops of Cashel, who had some ancient land interest in the area, acquired Fethard from the crown, and held it until the 16th century. However, the principal involvement of the Archbishop was in the vicarages of the rectories owned by the Hospital, including Fethard. It is possible that the Archbishops encouraged the process of borough development (and the similarity of the Fethard street plan to that of Cashel may be relevant here). It was the hospital that remained the major landowner near Fethard (Hennessy 1988).

Late medieval 14th – 16th centuries The street plan of Fethard implies some metrical regularity in its laying out, and possible accommodation for some 80 burgesses. The town flourished in its early phases, and an Augustinian priory was founded in 1305. A royal murage grant in 1292 may imply the creation or strengthening of existing walls. The intermittent violence of life on the ‘marches’ between Kilkenny and Fethard is likely to have made these walls a necessity. Later references to monies for repair, and further murage grants in 1409 and 1468 suggest that the walls were kept in good repair, and the evidence of the walls themselves seems to suggest a major late-medieval rebuilding, perhaps in the 15th century. Continuing urban activity is demonstrated by the presence of late medieval castles near the churchyard, rebuilding of churches, and the use of Fethard as an administrative centre for courts. The dissolution of the monasteries in 1540 saw the seizure of monastic land, while the institutions themselves often carried on regardless (the friars remained until the 18th century). The town was chartered in 1552 with government under a sovereign and provost.

16th – 17th Centuries The prominence of the Everard family in Fethard is a key to its success in the 16th and 17th centuries, with a new charter in 1607 and the rebuilding of the town hall (Tholsel) or almshouse (they also had a large town house). Thus the town had emerged from the period of greatest troubles when so many medieval towns vanished, as an active and apparently successful corporate market town.

. This was later evidenced by the growth of suburbs, and the gradual enclosure of the town’s open fields.

A Corporation in Decline 18th – 19th centuries Fethard Corporation became more prominent as the influence of the Everard family waned, but ran into decline in the eighteenth century, as so often in Ireland, and as so remarkably described by the Commissioners reporting on the Municipal Corporations in the 1830s. They found that the lands and property of the corporation had been squandered, and the corporation was abolished in 1840. But administrative decline may have occurred in a time of prosperity in the market area of Fethard, and the mills point to a flourishing grain trade before the Famine, and population peaked at nearly 4,000 in 1841 (falling continually ever since). Most of the town’s architecture is of this period, and the scale of the church, convent and quality of the housing points to prosperity.

19th and 20th centuries Fethard overcame the setback of the Famine years and continued to serve as a local agricultural centre with trades and minor industries. The railway from Clonmel to Thurles served the town from 1879 to 1967, and it has remained as a quiet, rather remote place, whose history has served to preserve the remarkable series of medieval monuments in the town.

SETTING AND CONTEXT

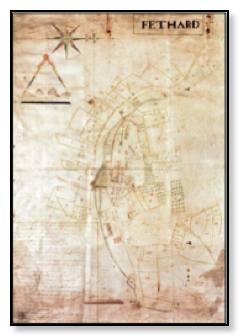

Fethard is located at a crossing place on the River Clashawley, on a low promontory above the flood plain, surrounded by a wider plateau of good farm land. The town had its own open fields, which are recorded on estate maps before their enclosure, and are an important reminder that ‘burgesses’ were as like as not farmers for some part of their existence.

The nodal position of the town on roads that were or became connecting routes is shown by the two bridges and five town gates. The notable absence is a castle, but this may be because the primary Norman settlement at Kiltinan was the location of the lord’s castle, which may mean that Fethard emerged as a town in a subsequent phase (it has been suggested as a foundation of the de Braose lordship, or yet later of the Archbishop of Cashel).

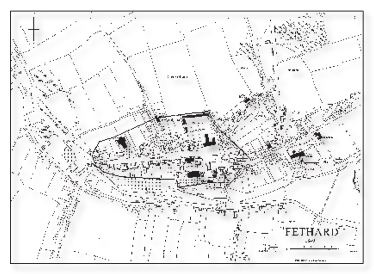

Map of Fethard 1840

THE MEDIEVAL TOWN: TOPOGRAPHY AND BUILDINGS

The plan of Fethard has been described at some length by O’Keeffe, and this can be summarised here by noting the large-wedge-shaped market street (similar to that in Cashel) and the ‘baffle-entry’ to the town through three of the gates.

The manner in which the walls relate to the burgage/tenement blocks is striking when compared with a place like Athenry. Whereas the latter is exceedingly generous in the amount of open land that was enclosed, Fethard’s urban properties were closely hemmed in by the walls in a manner that suggests the walls were following existing plots rather than accommodating future expansion.

The remains of the walls are very extensive and almost complete except in the south-east sector.

The full-height wall on the south has been partly restored in a previous programme of enhancement, and elsewhere the wall survives to near full height, but without its parapet.

There are few diagnostic features in the masonry fabric to determine dating, apart from the late medieval style of parapets (and the single arrow-loop by the water gate), and

it is not certain that the arch of the North Gate is medieval. One characteristic features

is the masonry walling, which is remarkably consistent in most standing lengths of wall.

This typically consists of large squared (or rather polygonal) blocks, laid in regular,

though not usually horizontal courses. This is quite distinct from coursed rubble or level

coursing of squared blocks, and the fact that the characteristic regularly/irregular masonry can be seen in most of the standing remains suggests that they may be contemporary.

Example of Fethard masonry on SW mural tower

The North Gate is an arch flanked by a tower, and the lost Madam Castle at the west gate was a large double tower over the gate, and it may well be that the lost gates also had adjacent towers or ‘castles’.

The group of urban castles around the churchyard are ostensibly individual palaces of great urban families, though the one in the church yard wall may have been a ‘vicar’s pele’ like those of northern England.

Whether Court Castle and Edmond’s castle could have functioned as adjuncts to a collegiate church is an intriguing possibility.

FETHARD, HISTORIC TOWN WALLS COUNTY TIPPERARY • JUNE 2009

![]()

![]()

LEVELS OF SIGNIFICANCE

. Basis of the Assessment The assessment of significance reflects the cultural and ecological aspects of the monument as a whole, particularly in relation to medieval walled towns in Ireland, while also assessing the sections of the site individually.

. Significance in other terms are taken into consideration, including an academic context and other values that visitors or users of the land may assign to the monument and its historical perspective.

. The components of the settlement are assessed individually, thus providing a detailed framework before being considered in a wider setting. This will be used to identify key elements and to highlight specific areas for consideration.

.

. Levels of Significance Initially, an assessment is made on the significance of the monument at three levels: national, regional and local.

. The monument can also be considered from four major aspects: intrinsic architectural and historical interest, historical association, and group (overall) value.

. Other factors considered include: the monument’s ability to characterise a period; the rarity of survival; the extent of documentation; association with other monuments; survival of archaeological potential above and below ground; its fragility/vulnerability; and diversity.

. Less tangible, but still vital to the significance of the monument, are the social and spiritual qualities which it represents. These can be formulated in the following fields: representative value (the ability to demonstrate social or cultural developments); historical continuity; literary and artistic values; formal, visual and aesthetic qualities; the evidence of social history themes; contemporary communal values; and the power to communicate values and significance.

. Degrees of Significance Measures for assessing the significance of Fethard in its various aspects have been based on all the above criteria where they have seemed relevant.

The degrees of significance adopted here are:

Outstanding Significance: elements of the monument which are of key national or international significance, as among the best (or the only surviving example) of an important class of monument, or outstanding representatives of important social or cultural phenomena, or are of very major regional or local significance.

Considerable Significance: elements which constitute good and representative examples of an important class of monument (or the only example locally), or have a particular significance through association, although surviving examples may be relatively common on a national scale, or are major contributors to the overall significance of the monument.

Moderate Significance: elements which contribute to the character and understanding of the monument, or which provide an historical or cultural context for features of individually greater significance.

Low Significance: elements which are of individually low value in general terms, or have little or no significance in promoting understanding or appreciation of the monument, without being actually intrusive.

Uncertain Significance: elements which have potential to be significant (e.g. buried archaeological remains) but where it is not possible to be certain on the evidence currently available.

Intrusive: items which are visually intrusive or which obscure understanding of significant elements or values of the monument. Recommendations may be made on removal or other methods of mitigation.

. STATEMENT OF OVERALL SIGNIFICANCE The overall significance of Fethard can be defined as follows: Fethard is of outstanding significance as a medieval defended town with its very complete circuit of walls and other medieval buildings demonstrating the life and trade of the town.

. KEY PERIODS OF SIGNIFICANCE Phase I: Prehistoric- Early Medieval Fethard Very little is known of Fethard before the Anglo Normans.

. Uncertain Significance Phase II: The Medieval Town: 12th to 16th century The medieval town wall survives almost in its entirety with many key elements intact. The Medieval and Post-Medieval layout of the town has been preserved and illustrates the importance of Fethard to the local economy as a defended market town.

. Additionally its topography and setting is almost unchanged and there is potential for discovery of more of the key elements. The level of survival of the town wall and layout makes Fethard.

. An outstanding representative of major local and regional significance, and so of outstanding significance.

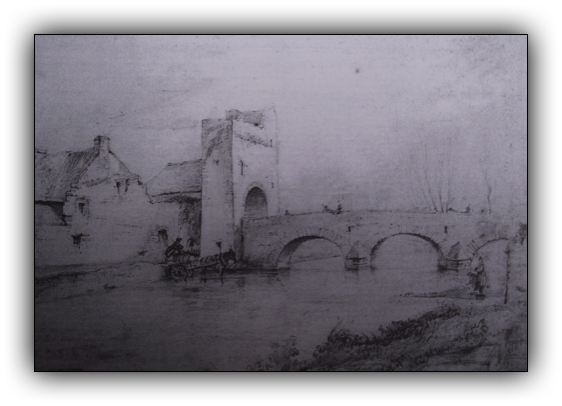

Madam Bridge from south east 1857, Du NoyerEarly Modern: 16th to 17th century

Post-Medieval expansion of the town and its significant survival and prosperity during and after the wars and religious struggles of the early modern period are evidenced in the surviving town wall and features from this period. The rate of survival makes the town an outstanding representative of local, regional and national importance and of considerable significance.

18th and 19th-century Fethard

The decline of civil administration simultaneously with the continued prosperity of the town from agriculture and its local importance even through the mid-19th century famine could be considered a reflection of the national situation.

The amount of surviving architecture of this period, and the scale of building demonstrates prosperity, while this period adds to the character and understanding of the town wall as it is seen today and provides an historical context to the changes which have occurred. It is therefore of contributory and therefore Moderate Significance.

Modern Fethard

The lack of an overall plan for conservation has led to damage and loss of various parts of the wall. Development has led to intrusion onto the wall and key features causing damage and restriction of access and view. This has resulted from insufficient understanding of the significance of the town. These omissions have resulted in actions which are Intrusive.

KEY ELEMENTS OF SIGNIFICANCE

Setting and Context The natural and landscape setting of Fethard is of considerable significance. There are a number of key views of the town that are significant for the appreciation of its setting, including views across the river town from the south, and from the approach roads descending from higher land.

The town can also be seen in the wider context of the medieval landscape that supported the town, including the nearby fields, and Market Hill commons to the south.

Ecology The ecology of the riverside and green spaces is of moderate significance for understanding the landscape history of the site, and for the biodiversity value they represent.

The Castles The surviving remains of the castles grouped around the churchyard are of outstanding significance as a demonstration of life in the medieval town.

The Medieval Town Plan

The street plan of Fethard is of considerable significance for preserving the medieval topography of the town.

Medieval Town Walls The medieval town walls are of outstanding significance for defining the area of medieval settlement, for the extent of the surviving elements), especially the association with the riverside and other medieval buildings on the south side, and also for the potential for further discovery below ground.

Medieval Buildings in the Town

The Churches and castles, and remains of older houses together form an exceptional group of medieval structures demonstrating the variety of urban building in a relatively small town, and are therefore of outstanding significance

Façade of Tholsel, Tadhg O’Keeffe, 1995

Archaeology

The evidence of past discoveries suggests there is some potential for discovery of buried remains of the medieval town, with a quality of survival partly arising from the lack of later destructive activity. This is of considerable significance.

Documentation

Although discontinuous, the documentary record of the site from the 13th to the 17th century is of moderate quality and significance, compared with other places.

Conservation and management Plan. - Oxford Archaeology June 2009

This plan has been written by Deirdre Forde, Georgina McHugh and Julian Munby of Oxford Archaeology. The steering group has been of considerable assistance, its members: Allison Harvey, Heritage Council; Damian O’Brien, Failte Ireland; Tim Robinson, Fethard Historical Society; Dóirín Saurus, Fethard Historical Society; Joe Kenny, Fethard and Killusty Community Council; Terry Cunningham, Teagasc; Peter Grant, Fethard Tidy Towns; Noel Byrne, Fethard GAA; Barry O’Reilly, National Inventory of Architectural Heritage (DEHLG); Pat Looby, Patrician Presentation Secondary School; Cllr. John Fahey, Chair South Tipperary County Council; Ann Ryan, C.E.D.O. South Tipperary County Council; Eoin Powell, S.E.E. South Tipperary County Council; and Hugh O’Brien, E.P. South Tipperary County Council. Once again it has been of great value to consult the fundamental studies by Adrian Empey and John Bradley on the history of the Norman settlement and towns, while in Fethard we have drawn heavily on earlier studies by Tadgh O’Keeffe. Margaret Quinlan has provided architectural advice methods. Tim Robinson has shared the results of his detailed research on the history of Fethard and, with others, provided welcome and hospitality in Fethard.